Contents

- A very brief history of home music recording

- Home music recording in the 1980s

- A note on MIDI

- Early electronic music production

- Home music recording in the 1990s

- What parts do I need for my computer for home music recording?

- Which CPU is right for music software?

- Updating your CPU at a later date

- How much RAM do you need for music software?

- How easy is it to upgrade RAM for music recording?

- What kind of storage should you use for home music recording?

- Do you need a graphics card for home music recording?

- What’s the best way to cool your system for music software?

A very brief history of home music recording

Let's begin by looking at how home music recording evolved. The story begins over 30 years ago.

Home music recording in the 1980s

Up until the 1980s, music production and recording was very much analogue.

While DAT tapes and digital recording formats began to appear towards the end of the decade, it wasn't until the early 1990s that audio editing on a 'computer' became possible.

One of the first pieces of digital recording equipment was a computer sequencer called the Fairlight CMI. It resembled a personal computer that allowed sequencing, when in fact it was actually a dedicated piece of hardware that did nothing else. Also, it was £30k. In 1982. Not exactly bedroom producer territory (although it did have a pretty neat 'touch screen' light pen though).

In 1985 Atari released the ST, a personal computer that supported Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) audio and featured built-in MIDI ports that allowed for sequencing of external hardware synthesisers (a pretty forward-thinking feature considering the team at Sequential Circuits had only invented it four years prior).

A note on MIDI

MIDI, or Musical Instrument Digital Interface, is a very Ronseal name: it does exactly what it says on the tin.

It is a digital (usually 7-bit or 0-127 values) control standard that allows electronic Musical Instruments to Interface with each other Digitally.

We’ll go into more detail on MIDI further on in this series.

Early electronic music production

So, back to the evolution of home music recording.

Early electronic music was created with tons of devices synced together with sequencers, which were both expensive and difficult to program.

The Atari allowed people to compose and arrange music on a display, with a much more powerful and intuitive interface that really opened up music production to a lot more people. The Atari was a home computer after all.

The most popular sequencers for the Atari were developed by Steinberg; Pro 24 and eventually Cubase 16.

Whilst Pro 24 was powerful, some magazines at the time were critical of its interface and found it difficult to use. Cubase solved that issue in 1989.

Then the 1990s happened…

Home music recording in the 1990s

Where the 1980s had been the birth of sequencing and MIDI, the 1990s was the era of audio.

Cubase Audio for Mac was released in 1991 and Creative released the Sound Blaster 16 in 1992, which supported 44.1 kHz sampling and 16-bit sample depth (CD Quality) recording.

Things got a lot more spicy in the latter half of the decade with Steinberg (you’ll see this name a lot) releasing Cubase VST in 1997. This was the introduction of multi-track recording and digital effects on a computer.

1999 saw the introduction of the ability to ‘plug-in’ effects to the Cubase software. This opened the floodgates for developers to create their own software synthesisers and effects that could be loaded into a Digital Audio Workstation (DAW).

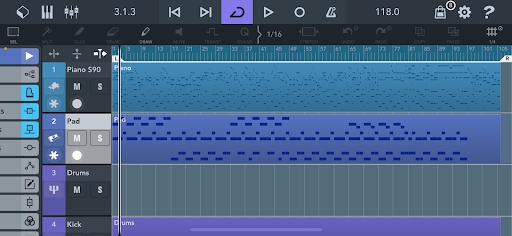

Cubasis 3 running on an iPhone 12.

Okay, with that very brief history out of the way, how about some meat to go with the potatoes? (Vegan alternatives are available).

The flood of plug-ins that arrived at the turn of the Millennium has grown into an entire industry. Plug-ins from major brands such as Native Instruments and Waves are now staples in most producers’ tool belts.

So, if you want to start creating music, you might be wondering what specific requirements your computer will have to meet? Well, in all honesty, there are no specific requirements, but there are a plethora of considerations that will make a huge difference to how smooth the whole venture goes.

What it comes down to is this:

Do you want to use more plug-ins? Then you’re going to need more PC to run them.

Why not just buy a Mac for home music recording?

You could, and a lot of people do!

One of the best features of Macs is Core Audio, which basically makes most audio interfaces ‘plug-and-play’ and is low-latency. It’s essentially ASIO for macOS (we’ll come back to ASIO later in this series).

Additionally, macOS also has the option to create aggregate audio devices. What is an aggregate audio device? It’s where the operating system combines multiple physical audio interfaces into one virtual audio interface and is one feature that we really wish was included on Windows machines.

Developers and Macs

Due to there only being a limited number of hardware configurations (or SKUs) for the Mac ecosystem, developers can program their software for known hardware.

This allows the software to be better optimised and increases stability. The flip-side of this coin is upgrades.

Having a tightly controlled hardware platform makes upgrades expensive at the time of purchase and difficult (if not impossible) later down the line. Apple as a company is very defensive about its hardware and likely won’t look at hardware you’ve been inside of.

The transition to Apple Silicon

Apple’s Mac hardware is currently in a state of transition with Apple Silicon (Apple’s move from using Intel processors to Apple’s own silicon).

Despite the best efforts of Apple to make x86 apps (which Intel CPUs used) work on their new hardware, a lot of audio software developers are advising that everyone wait until their software has been fully ported to the Apple Silicon architecture.

Additionally, whenever Apple updates macOS, a lot of software developers and hardware manufacturers often advise users to wait for patched software in order to function on the new macOS. Some software developers also use this as an excuse to charge users for the update (we’re looking at you AVID).

Mac-only audio software

It’s also worth noting that leading music software such as Logic Pro is only available on Mac.

There are also a large selection of virtual instruments and effects that only run on Mac. The installation process of software and plug-ins is also fairly standardised in the Mac ecosystem and often makes the process of adding new plug-ins as painless as possible.

Multi-device Mac music editing

If you’re the kind of person who also makes music on your iPhone or iPad, you can integrate your portable device into your computer setup.

Firstly, you can stream audio and MIDI from your phone via a lightning cable with minimal configuration. Additionally, Apple has added support for iOS AU (AudioUnits) into macOS Big Sur (providing developers allow this functionality of course).

Mood Model 15 iOS plug-in running natively on Mac Pro. Source: MoogMusic.com

If these features appeal to you and might fit your workflow, you should seriously consider joining the Mac ecosystem (although we'd suggest you wait for the new Apple M2 chip).

Our advice is to buy the best Mac you can afford.

If you want to go the Windows route, or don't know what to upgrade on your Mac, keep on reading.

What parts do I need for my computer for home music recording?

Are you having a tough time picking the right parts for your PC or deciding which version of Mac to get for home music recording?

Here, we’ll discuss which parts to consider for your system, which upgrades will give your system the biggest boost and which ones can wait until later.

Which CPU is right for music software?

When it comes to picking a CPU for music software, should you focus on more cores or better cores?

In my current music PC I’m using a Ryzen 3700X. At the time I built it, it was the latest iteration of Ryzen. If I was only going to be using it for gaming, I’d have stuck with the Ryzen 3600, but the extra cores of the 3700X allowed a little more longevity and allowed for more demanding plug-ins and workloads.

Conversely, one of the other team members at CCL recently upgraded to the Ryzen 5900X, but their budget and performance demands were much higher.

Generally speaking, plug-ins that generate audio tend to favour more powerful single cores. So, electronic music production would be possible using something like an AMD 5600X or even an 11600K from Intel.

Mixing effects however, tend to prefer multi-threaded performance. Perfect all-rounders don’t really exist, but the 8-core or more, latest-generation processors seem to strike the best overall balance.

Updating your CPU at a later date

In terms of upgrading your CPU, doing this at a later date will almost certainly require a new motherboard (or at the very least a BIOS update) - unless you are upgrading within the same generation.

For example, if you are upgrading from a Ryzen 5600X to a Ryzen 5700X, or going from an Intel i7 9700 to an Intel i7 10700 you won’t require a new motherboard. Upgrading a CPU in a laptop is impossible, unless you’re very handy with a soldering iron.

How much RAM do you need for music software?

Probably the second most important question after the CPU, is how much RAM do you need for recording music on your computer?

The short answer is: lots.

The long answer is a bit more complicated.

As you may be aware, the minimum recommended RAM for regular computer usage is 8GB.

However, recording music is definitely not normal usage. We’d recommend 16GB of RAM as an absolute minimum, however if your music projects are going to involve plenty of sample libraries or audio tracks, you may want to consider upping the RAM to 32GB (if not more!).

When it comes to using large audio samples or recordings in your music, RAM alone won’t be enough to hold your current project. Your DAW is pretty smart about its usage of RAM and will stream recordings from the storage drive instead of loading them into memory. So, in that instance, you’ll want a fast SSD - especially if you’ll be working with a lot of audio.

How easy is it to upgrade RAM for music recording?

RAM is one of the easiest parts to upgrade in a desktop PC.

Provided you have enough RAM slots available, you can easily buy another set of the same RAM and double your memory, or even quadruple it if you only have one stick and three slots available.

If you are already using all of your RAM slots, you will need to remove all the RAM in the system and start again. For example, if you wanted to upgrade from 32GB of RAM, you would have to replace all of your existing RAM (if it was 4x8GB) and use 16GB sticks or higher.

When it comes to laptops, RAM upgradability varies from laptop to laptop.

Note that an M1 MacBook cannot be upgraded at all as the RAM is soldered to the CPU, while other laptops will have a ‘door’ on the bottom to slide in more RAM. In summary, when researching your laptop, look for how many SO-DIMMS are on the spec sheet and the maximum upgradable RAM.

What kind of storage should you use for home music recording?

Storage is a challenging question and varies from workflow to workflow.

We generally suggest that you have at least a 256GB SSD for the operating system and programs (or consider 512GB to be on the safe side).

You should then think about having an additional 128GB (or larger) SSD for your current music projects, to remove the IO bottleneck that can occur. You should also think about a hard drive for longer-term storage purposes.

If you’re the kind of person that uses large sample libraries, it may be worth getting an additional SSD for this. Buy one that’s as large a capacity as you can afford, as it’s likely your sample library will be constantly growing.

In my dedicated music computer, I have a 512GB NVMe drive for the operating system and programs (and a game or two), a 2TB HDD for documents and mid-to-long-term storage, a 256GB SSD for current projects (and Cyberpunk 2077) as well as a 512GB USB SSD for my sample library (which also needs upgrading). The other team member we mentioned earlier has two 1TB NVMe (in RAID 0) for the operating system, programs and all his games, two more 256GB SSDs for sample libraries (also in RAID 0) as well as a 3TB HDD for general storage and programs.

A note on RAID

Do you need to go with RAID 0?

No… in fact it’s a sure-fire way of losing data. Unless you make backups, you’re essentially doubling your chances of a drive failure. However, if you want speed, it’s a good choice.

Newer PCI-e Gen 4 SSDs are up to twice as fast as their 3.0 equivalents and are excellent if you don’t mind the extra cost. Generally speaking, desktops can have their storage upgraded by popping another HDD or SDD in the case and connecting a few cables. Otherwise, you can add more storage by connecting a USB HDD or SSD.

Do you need a graphics card for home music recording?

Whether or not you need a graphics card depends on which CPU you have chosen and the music software you want to use.

If you’ve chosen an Intel CPU and it doesn’t have an ‘F’ in the model number (e.g. Intel 9900KF doesn’t have a GPU, while the 9900K does) or your AMD CPU doesn’t end with ‘G’, you’re going to need a separate graphics card.

Don't despair though! The good news is that you don’t have to buy a high-end card.

For the most part, music software is not GPU intensive. There are some plug-ins (such as Wave plug-ins) which do use some GPU power to make their user interfaces look pretty, but chances are you could get away with a GTX 1050 Ti and not really worry about graphics for the foreseeable future.

If you pick FL Studio as your DAW, bear in mind that the UI is GPU accelerated. Also, plug-in windows don’t auto-close, so when you’ve got a lot of them open, it’ll quickly load up the GPU. The F12 button if your friend (it closes all windows).

What’s the best way to cool your system for music software?

What’s the best cooling system for dedicated music PCs? It’s the subject of debate between advocates of air-cooled systems and advocates of water-cooled systems.

My dedicated music PC uses an all-in-one watercooler, with the rest of the system fans from beQuiet! The system is incredibly quiet under the load of music production. Conversely, the other team member we mentioned earlier uses air-cooling for his system, with 140mm fans that move more air whilst spinning less.

Bigger fans tend to move more air at a lower RPM, which means you get less motor noise. If you’re recording audio in the same room as your PC’s tower, it’s best to minimise the bearing/motor noise.

The noise produced by air moving around and interacting with the case is very similar to white noise, which pretty much every DAW on Earth is capable of removing easily. Of note, however, is that larger fans often have lower static pressure (their ability to push or pull through restrictions. So, if you have a case that doesn’t have a lot of ventilation (or has a lot of filters), you may be better with smaller fans.

Which is all a long way of saying, when it comes to cooling try and pick the quietest option you can find.

Conclusion

The applicability of much of the advice of this article depends on what kind of music you want to make and what you want to do with your PC.

If we had to sum up our advice into a few short paragraphs it would be as follows.

Begin by selecting the best CPU, from the latest series, you can afford. If you want to go down the Mac route, it’s likely your RAM will be capped at 16GB for the Apple Silicon Macs (which at the time of writing is a £200 upgrade). The next generation of Apple Silicon may allow for more RAM, but only time will tell.

You should aim for at least 256GB of storage inside your system to start with (or at least 512GB if it’s a Mac or laptop that you can’t upgrade at a later date). If you need more storage for sample libraries or project backups, an external HDD or SSD is a great choice (choose internal storage if it’s a Windows desktop).

Coming next time...

In the next article we are going to discuss the software to go with your system. We’ll explain the difference between a VST and an AU, what a DAW actually is (and why you need it), and we’ll delve into a bit more detail on what MIDI is and what it’s for.

If you’ve got any questions, feel free to ask them in the comments and we’ll try and answer them!